All over the world, governments are reacting to stop the spread of Coronavirus by implementing strict stay-at-home orders or quarantine laws.

Governor Gavin Newsom of California recently ordered all Californians to shelter in place until further notice in response to the growing pandemic. The Order requires all Californians who do not work in essential fields to stay at-home except for necessities like grocery shopping, medical care, and exercise. At all times, the Order also requires the public to practice social distancing. ‘Social distancing’ is the practice of maintaining physical distance of approximately 6 feet between other members of the public in order to slow down the spread of an infectious disease.

All non-essential businesses are required to keep workers home. The Order allows industries deemed essential to remain open and operational, like healthcare, food and agriculture, and public utilities.

Importantly, the Order is enforceable under California law and punishable by imprisonment or a fine under Government Code section 8665.

New York issued a similar order on Friday March 20, 2020, where Governor Andrew Cuomo requested New Yorkers to stay home as much as possible. He restricted gatherings to under 70 people and enacted more strict rules of businesses. Governor Cuomo fell short of calling his order “shelter in place” because of the connotation those words evoke, such as active shooter situations or nuclear war. New York Police launched new patrols routes so officers can encourage people to stay inside.

These orders highlight the extreme authority the government has in times of emergency to restrict the freedom of movement and civil liberties of the public. But how far does that power go?

Federal and State Government’s Authority to Quarantine

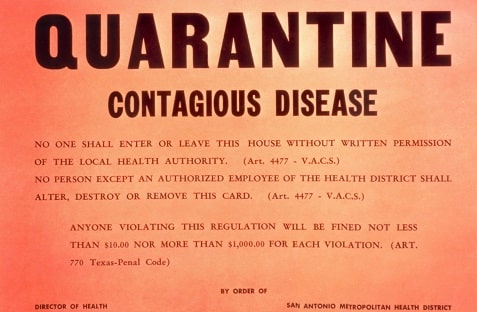

A quarantine is meant to restricts movement of people exposed to a contagious disease to see if they become sick and remove them from contact with other people. Historically, quarantines have been a successful method of stopping outbreaks of contagious diseases. Quarantine has its origins in Europe following outbreaks of the plague and tuberculosis.

There is little case law on the quarantine power of federal and state governments, but courts have recognized the government’s power to quarantine since 1824. In Gibbons v. Ogden, the Supreme Court struck down a New York law that restricted steamboat navigation in New York waters. The Court held the state regulation was inconsistent with the Constitution. Importantly, the Court declared that laws of regulation of internal trade and navigation belong to the states to regulate—as do quarantine laws, inspections laws, licenses to sell goods, and other similar laws that promote the public’s interest.

Although the Court declared that quarantine laws are within the power of the state, Chief Justice John Marshall goes on to say in Gibbons that the federal government has the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations and “among states.” Meaning, the federal government could theoretically exercise the same power to quarantine.

Importantly, the Supreme Court’s decision in Gibbons serves as the basis for the Commerce Clause doctrine, which gives the federal government the power to quarantine. The Commerce Clause of the Constitution allows Congress to regulate anything that touches upon interstate commerce.

The Commerce Clause doctrine was expanded in 1942 when the Supreme Court decided Wickard v. Filburn. In that case, the Court upheld a federal statute that penalized farmers who exceeded established wheat production quotes. This case is important because it allowed the federal government to regulate activity that occurred wholly within a state, even where wheat was not sold commercially. This decision authorized the federal government to regulate activity that has a “substantial economic effect” on interstate commerce—meaning it could regulate things that were previously under the power of the states.

However, the Supreme Court later reeled in the power of the Commerce Clause in United States v. Lopez in 1995. In Lopez, Congress passed a law that made possessing a gun within 1,000 feet of a school a federal crime. The Court struck down that law because its regulations of gun ownership did not touch upon commercial activity and affected guns that did not travel in interstate commerce. Thus, the Court limited the federal government’s regulatory power established by Gibbons.

Since Lopez, the Court has gone back and forth in reducing and expanding the federal government’s power under the Commerce Clause. See United States v. Morrison and Gonzales v. Raich. The Supreme Court’s decisions relating to the Commerce Clause doctrine has ebbed and flowed over the last century. But given the current ideological makeup of the Supreme Court, it is likely a broad exercise of federal power to quarantine would be upheld.

Based on that power delegated to the federal government by the Commerce Clause as established in Gibbons, Congress passed the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C section 264) in 1944, which codified the federal government’s quarantine authority.

Under Section 264, the Secretary of Health and Human Services may take measures to prevent the entry and spread of disease into the United States and between states. Section 264(d)(1) allows the government to detain and examine anyone who is a probable source of infection. If that person tests positive for a disease, it can detain him or her for whatever time is reasonably necessary and by any means. This essentially would allow the government to indefinitely detain someone with a communicable disease in whatever manner it wants.

The Secretary has broad power to take any measure in response to a public health concern or to prevent the spread of disease. The federal government can also accept assistance from state and local entities in enforcing quarantines and vice versa can lend its resources to them.

The Secretary delegated to the Center for Disease Control the ability to physically detain and examine people entering the country. The federal government already exercises its quarantine authority regularly at our borders by quarantining persons entering the country to prevent the spread of communicable diseases.

Although the true extent of its power to quarantine has not been tested, the federal government theoretically can enact any law that regulates interstate commerce, which is a broad power, and can exercise its quarantine power in response to a public health concern. On paper, these powers seemingly have no limit.

Police Power

States are responsible to enforce any quarantine or shelter-in-place orders because the individual states have police power under the Constitution. So far, no state has taken widespread action to enforce quarantine orders via law enforcement. Governor Newsom said he does not think, at this point, that police power will be necessary. Although there are some reports of law enforcement actively breaking up gatherings in California.

If the federal government enforced a quarantine, enforcement would be coordinated with states, but would largely fall on the states to carry out.

We are seeing coordination already between the state and federal government as the Coronavirus pandemic unfolds. The federal government activated the National Guard this week of March 22, 2020, so they could assist communities with responding to the Coronavirus. In some states, the National Guard is working at and guarding food banks, and in other states they are moving supplies and restocking shelves. President Trump said the states would have “maximum flexibility” to use the National Guard, meaning the National Guard will act at the direction of the governor of each state.

Every state is using the National Guard differently depending on their needs. Governor Henry McMaster in South Carolina requested the Guard to draw up plans to construct temporary medical facilities next to hospitals. The Guard in Maryland is transporting cruise ship passengers’ home after quarantine at a Georgia air base.

The federal government is also paying the cost for activating the National Guard, which the individual states would have to do if they activated their National Guard members.

What would a Quarantine Look Like?

It is unclear what a federally mandated quarantine would look like. Analogous laws may give context for the extent the government may be able to go in restricting people’s movements.

For example, state mental health laws allow the government to commit someone who is a danger to themselves or others. In California, Welfare and Institutions Code section 5150 allows a peace officer to take someone who is a danger to himself into custody for evaluation for up to 72 hours. New York has a similar law under its Mental Hygiene Law. Theoretically, a quarantine could look similar.

Activation of the National Guard is meant to help the public, it has arisen fears of Martial law and concerns the Guard will be used to enforce stay-at-home orders.

It remains unclear the extent the government will go to enforce orders to stay home or institute quarantines. However, one thing history tells us—in times where the public’s safety is in jeopardy, the government takes broad measures at the expense of the public’s liberties.